Crew Member

Age: 25

Hometown: Munich, Germany

Occupation: Night steward

Location at time of fire: Passenger decks, portside dining room

Survived

Wilhelm Balla was born on March 28, 1912 in Castrop-Rauxel, near Dortmund in the Ruhr Valley. His parents, Gottlieb and Wilhelmine Balla, had moved there from East Prussia at the turn of the century, and his father worked as a coal miner. Willy Balla was the first of 12 siblings, with his youngest brother, Helmut, having been born in September of 1927 when Balla was 15 years old.

their mother, Wilhelmine, age 22; Hermann, age 1, stepsister Änni, age 6.

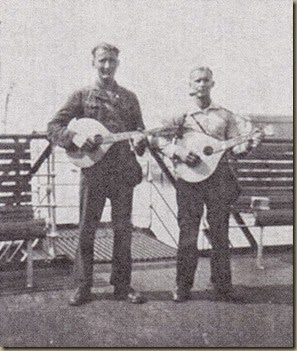

After finishing primary school, Balla began an apprenticeship as a waiter at the Hotel Lindenhof in Dortmund. However, within a few years the Great Depression had caused Germany’s economy to implode for the second time in as many decades. With rampant unemployment making jobs scarce, Balla and one of his good friends wandered throughout Germany, Austria, Italy and Switzerland, where they earned their living for the next couple of years as itinerant laborers, picking up whatever odd jobs they could find at factories and farms. They were also both pretty fair mandolin players, which earned them a few extra pfennigs here and there.

Willy Balla and friend playing their mandolins during their Wanderschaft.

By 1932, Balla had returned to Germany, where he attended a servant’s school in Munich and worked for the next several years as a butler in aristocratic houses, and also as a restaurant waiter. It was during this time in Munich that he met a young lady named Albertina Brandl. Willy Balla and Tina Brandl were married in 1936, and they would remain together for the next 52 years.

Albertina Balla, mid-late 1930s

Though he had grown up in Westfalia, Wilhelm Balla came to view Munich as his second home. But as he would later write in his journals, he would periodically wrestle with his own wanderlust, and he dreamed of traveling not just throughout Germany and Europe as he had done, but of visiting other lands – Africa, South America, the United States. With the rapid advancements in aviation since the first world war, what Balla really wanted was to fly to these places via airplane or airship.

Wilhelm Balla feeding the pigeons in Odeonsplatz, Munich, circa 1936

One day, Balla happened across a newspaper article about the LZ 129, Germany’s latest (and as-yet unnamed) Zeppelin, which had been under construction for several years. The article stated, “The new airship is nearing completion in the Zeppelin hangar in Friedrichshafen and is designed to carry passenger and mail traffic to South and North America.” Balla, like so many of his countrymen, had followed the exploits of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin and had read with great interest of the airship’s flights across the ocean, wondering how (or if) he would ever be able to afford the 1,500 Reichsmark fare to South America – roughly a year’s wages for him at the time.

It occurred to Balla that with his experience as a waiter and a butler, he was easily qualified to be an airship steward, serving the wealthy passengers whom the Zeppelins flew to and fro across the ocean. The only problem was, there were hundreds of applicants vying for roughly half a dozen open steward positions aboard the new LZ 129. His chances at landing one of these coveted jobs seemed exceedingly remote.

Then, Balla hit upon a clever plan. By chance, he had heard that Dr. Ludwig Lehmann, the father of the new airship’s commander, Captain Ernst A. Lehmann, also lived in Munich. Balla went Dr. Lehmann’s house, introduced himself, and begged Lehmann to speak with his son on his behalf and ask if he would help him to secure one of the steward jobs. Dr. Lehmann was apparently impressed by the young man’s audacity, and a couple of weeks later Balla received a letter notifying him that he had indeed been hired by the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei as one of the LZ 129’s stewards.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

On January 20, 1936, Wilhelm Balla arrived at the Zeppelin works in Friedrichshafen, where the finishing touches were being put on the LZ 129 prior to her inaugural test flights. The new airship would not be ready to begin making these flights for at least another month or so, but in the meantime, Balla had been asked to report for duty immediately so that he could familiarize himself with the Zeppelins by working with the maintenance crew that was overhauling the Graf Zeppelin. One of a Zeppelin steward’s duties was to answer passengers’ questions about the airship, and assisting with the work being done on the Graf Zeppelin would serve as a good crash course in the construction and operation of these sky giants.

Balla would later recall that first day in his journal:

When I entered the hall, I could not believe my eyes . Before me lay the airship Graf Zeppelin, which had so often crossed the South Atlantic. The underside of the ship was being repaired, and the outer cover was partly removed and being replaced, because the ship would not be flying again until early March.

Herr Feucht of the Zeppelin works led Balla on a tour of the Graf Zeppelin, showing him the interior of the gondola that housed the ship’s bridge, her radio room and kitchen, and her well-appointed passenger lounge and cabins. Then Feucht led Balla through a small door and into the ship’s interior.

We stepped inside the airship. I was never more surprised than by what I now saw, which was simply unbelievable to me. The entire ship’s interior above me was empty, 32 meters high and a length of about 200 meters, nothing but girders, struts and bracing wires. “Yes,” Mr. Feucht said, “the ship is empty now, but in a few days we’ll be installing the 16 gas cells. You will help with that.”

We walked along the keel catwalk, which was only half a meter wide, and half a meter below that was the bottom of the ship – the envelope. Foreman Feucht said, “Don’t step off of the edge, or you’ll have your own private air voyage all the way to the ground.” So, at first I walked as carefully as possible, as I valued my life, however in time I became so experienced at it that I could have run along the catwalk blindfolded.

For the next month or so, Balla assisted with the work being done on the Graf Zeppelin to prepare her for the new flight season. He not only helped to install the refurbished gas cells, but he also used an electric riveting hammer as he and the construction crew replaced worn and damaged girders and latticework. Balla also accompanied Chief Steward Heinrich Kubis on a tour of the almost-completed LZ 129 which, with more advanced design and extensive passenger accommodations than the LZ 127, astounded him almost as much as his initial tour of the Graf Zeppelin had.

At last, on March 4th, 1936, Balla joined Chief Kubis and fellow stewards Eugen Nunnenmacher and R. Keuerleber aboard the new airship’s first test flight. Although the ship carried no passengers on this flight, only Zeppelin Company representatives and political officials who were aboard as observers, Kubis wanted to make sure that his team of stewards were thoroughly familiar with the passenger accommodations. It was a short flight. The LZ 129 spent three hours flying over Friedrichshafen and Lake Constance as the command crew tried out the controls and the mechanics made sure that the engines were in order. However, the flight made a deep and lasting impression on Balla, who had long dreamed of seeing the world from above.

The next day they made another test flight, this one of 8 hours duration so that the ship could receive its official certificate of airworthiness. This time, Balla and the other stewards served a breakfast of beef soup and a lunch of Hungarian goulash. To Balla’s delight, the LZ 129 also flew over his adopted home town of Munich, where the citizens poured out into the streets to see the new airship, waving enthusiastically and sending loud cheers aloft.

After about two weeks of trial flights, during which Balla and the rest of Chief Kubis’ stewards settled into their routine of duties serving full multi-course meals and attending to a variety of passenger needs, the LZ 129 finally received her name. Though there was no official christening ceremony, the new ship would now fly under the name Hindenburg.

The Hindenburg’s first flight after her name had been painted in two-meter tall red gothic letters alongside her bow was a four-day cross-country flight, along with the Graf Zeppelin, during which the airships would promote Hitler’s move to remilitarize the Rhineland. This flight is especially notable to historians not only for the fact that it was a blatant propaganda stunt on behalf of the Nazi government, but also because a botched downwind takeoff at the start of the flight damaged the Hindenburg’s lower tail fin and necessitated repairs and a second takeoff later in the day.

However, for Wilhelm Balla, the flight was even more noteworthy because they flew over the village of Castrop-Rauxel, where he had grown up and where his family still lived. Everyone in town turned out to see the new Zeppelin, of course. As Balla later learned, his youngest brother Helmut watched the airship with his schoolmates. When young Helmut excitedly informed them that his brother was one of the Hindenburg’s crew members, his stock among his classmates rose tremendously and they all gathered around him, eager to hear more about the mighty Zeppelin floating above them.

All of this was merely prelude, however, to the flights that followed. Balla had been fascinated by the sight of his homeland from above, but his true passion was for flying to the exotic foreign lands that he had long dreamed of visiting by air. The day after the Hindenburg landed at Friedrichshafen after her four-day propaganda cruise over Germany, Balla and the rest of the stewards joined Chef Xaver Maier and his kitchen staff in provisioning the ship for its first four-day flight across the South Atlantic to the new airship port near Rio de Janeiro. Together, they loaded enough food, beverages and ice onto the Hindenburg to keep 91 passengers and crew fed for the duration of the four-day flight. As they stowed everything on broad food storage platforms alongside the keel walkway, Balla and his comrades took care to situate the perishable items so as to prevent them from spoiling as they flew through the hot equatorial climate.

the Hindenburg’s innovative all-electric onboard kitchen.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Then the stewards went through the passenger cabins, polishing the fixtures and putting new linen on all the beds, before seeing to the common areas and making sure that all was in perfect order for the arrival of the 37 passengers the next morning, March 31, 1936. Balla helped to show the guests to their cabins, and would later recall the unexpected difficulty of communicating with people who were from many different countries, who spoke a variety of different languages.

When everyone was aboard and the last freight and mail had been stowed, the Hindenburg prepared to depart. Balla stood at one of the broad observation windows alongside the passenger decks, listening as a military band near the hangar played the old Swabian folk song “Muß i' denn, zum Städtele hinaus.” He solemnly reflected on the gravity of the moment: at long last he was finally going to see Brazil – not merely from the air as he’d always imagined, but from the unique vantage point of the most advanced and comfortable mode of air travel that mankind had yet devised. As Balla pondered his good fortune, the ground began to drop away, as if on cue. The ground crew having released the airship, it ascended silently and, to those aboard, almost imperceptibly – aside from the fact that the well-wishers on the ground below suddenly appeared to be growing smaller.

Wilhelm Balla was the Hindenburg’s night steward, and so a great deal of his regular duties would take place while most everyone else aboard was asleep. He would clean the now-empty dining room and the lounge as well as the rest of the common areas, and would respond when passengers pushed a button in their cabins to request assistance. As they would in a fine hotel, the passengers would leave their shoes outside their cabin doors at night to be shined, and Balla would make sure that they were all gleaming like new by the time the passengers awoke the following morning. But when his duties were finished, instead of going straight to bed, Balla would often sit next to the large observation windows in the empty passenger lounge. He would later remember how eager he was to spend every free moment at the windows on that first flight over the ocean so that he wouldn’t miss anything, watching the sea sliding by in peaceful silence below at night and, during the day, marveling along with the passengers at the islands, schools of fish and occasional steamship that would appear below as they flew over the South Atlantic.

outside of his cabin for the night steward to shine.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Balla’s night shift also gave his crewmates a perfect opportunity to indulge in an old mariner’s tradition. Balla would later recall:

On the third day of the voyage, it was just about three o’clock in the morning when the phone near me rang. One of the mechanics on duty told me that he’d seen a passenger wandering along the keel walkway, and that I should go and check to make sure that everything was in order. Since this sort of thing wasn’t permitted, I headed straight for the walkway. So, I was innocently strolling along the catwalk when suddenly I got an massive amount of water poured over my head. I stood there, looking like a drowned rat when I heard loud laughter above me and looked up. I saw there up in the girders three men holding buckets, having just played a corker of a practical joke on me. So, this was the famous equatorial baptism! As proof, I was presented with a baptismal certificate. I was naturally very proud of this.

The certificate, one of which was presented to each passenger and crew member on their first flight to

South America, was drawn by Dr. Eckener’s brother Alexander, a professional painter and printmaker.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Early on the morning of April 4th, after almost exactly 4 days in the air, the Hindenburg arrived over Rio de Janeiro just before dawn. The sight was not one that Balla would forget:

It was still dark when Rio appeared, a sea of lights spread out before us. We had reached our destination! It was too beautiful, to see this magnificent city from above in all her blazing splendor. I had to keep asking myself, “Am I dreaming, or is this reality?”

The following month, Balla realized yet another one of his dreams as the Hindenburg made her first flight to the United States, where she would moor at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, NJ, about 50 miles south of New York. This time the airship took off from Friedrichshafen in the evening, and by the time they reached the English Channel it was too dark to see much of anything.

I was on night duty and could see the beacons and the coastal lights. Around 3 o’clock in the morning, Captain Lehmann came up to me in the passenger lounge. We sat down in the writing room and talked for about two hours about everything under the sun. He couldn’t sleep, and was happy to have somebody to talk to. I often wondered about the fact that he got so little sleep. He was simply very conscientious, and always wanted to make sure that he had everything under control.

Toward morning, the first passengers were already coming out of their cabins, so as not to miss the sunrise. I was relieved at 6:00, and looked forward to getting some sleep.

Two days later, in the wee hours of the morning, the Hindenburg reached the east coast of the United States, arriving over New York City at about 5:00 AM. The sun was just rising, and New Yorkers climbed on the roofs of buildings and craned their necks for their first look at the new Queen of the Skies. Wilhelm Balla was still on night duty, and was astounded by what he saw.

When we reached the Statue of Liberty, a concert of sirens began that I never experienced again. Every ship in New York’s harbor joined in, stopping only when we flew on once again. Likewise, it was the first time the people of New York had been able to greet us. Then we flew over New York’s skyscrapers. I cannot describe in words the kind of impression that this made on me.

After circling the city, a crowd-pleaser for the passengers which would become a tradition on subsequent flights to Lakehurst, the Hindenburg flew on to Lakehurst. The airfield was packed with throngs of people anxious for a close look at the new airship, and guards were stationed around the visitors’ area to keep spectators clear of the mooring area. Balla watched as the US Navy ground crew expertly connected the ship to her mooring mast and guided her into the vast airship hangar.

Now as I climbed out of the ship and tried to leave the hangar, I was instantly surrounded by hundreds of enthusiastic Americans who blocked my way. Now I had achieved a bit of a celebrity status, because everyone around me demanded my autograph. It took me over an hour to make it a couple hundred yards to the hangar exit. As soon as I left the hangar, I suddenly found myself sitting in a car that was parked there and was pressured by its occupants into driving to New York with them. It was a sincere invitation, and they would fulfill all of my wishes if I would do them the honor of riding along with them. Owners of other cars made the same offer to my comrades. For these people we were, quite simply, a sensation.

After nearly four days of being treated like royalty by their newfound American friends, Balla and his comrades welcomed a new group of passengers aboard for the Hindenburg’s return flight to Germany. This time, rather than landing at Friedrichshafen, they landed at what was to be their new home base – the Rhein-Main airfield at Frankfurt. Balla and his wife, Tina, moved to a house in Walldorf, a village just south of the airfield where most of the Hindenburg’s crew would live while new homes were being built for them in the new town of Zeppelinheim, just to the northeast.

After the second flight to South America at the end of May, the Hindenburg was put in the Zeppelin works hangar at Löwenthal for minor repairs and to have some additional features added. One of these new additions quickly became a favorite of Balla’s. In the extreme bow of the ship, among the mooring platforms from which crewmen handled the forward landing lines during takeoffs and landings, a new observation area was installed. On either side of the keel, a small bench and table were bolted to the framework, with a long vertical window in front of each.

I, myself, would often choose this place, as it had the most wonderful view, especially when there was something interesting to see. […] It is hardly possible to describe how beautiful the view was. […] If I had time off duty, I would often spend hours at the window in the bow watching the activity on the various islands that we would fly over. Sometimes I would even wish I could be dropped off on one of those islands and then be picked up again on the homeward voyage. Naturally, this was just wishful thinking. I was a crew member of the LZ 129 Hindenburg, and had duties to fulfill aboard her.

(photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Wilhelm Balla made every one of the Hindenburg’s subsequent flights, and would later write a journal of his experiences. In the journal that he later wrote recounting his experiences as a Zeppelin steward, Balla captured many details about his day to day experiences aboard the Hindenburg. Many from the ship’s early flights have already been recounted here, but the remainder of the 1936 flight season was to prove as memorable to Balla as the beginning had been.

When the Hindenburg was moored at Lakehurst, Captain Lehmann would grant visitor passes to various people, often VIPs, and Balla was often the crew member who was assigned to lead these special guests on tours of the ship. In this way, he got to know and become friends with a great many Americans, many of whom would take him into New York on day trips.

In addition to his night duties, Balla would also serve passengers during the day (when he wasn’t sleeping after his shift was over at 6:00 AM, of course.) He would make his way forward to the ship’s radio room where the radio operator would hand him the latest edition of the daily onboard newspaper, which would provide passengers with the latest news from around the world. Balla would pin the paper to the bulletin board at the head of the gangway stairs in the central cabin area, where there was also a map of the world on which the ship’s current position was marked in red pencil.

In August, the Hindenburg flew over the opening ceremonies for the 1936 Olympic Games. In addition to the spectacle of viewing Berlin’s massive new Olympic Stadium from the air, Balla would also remember one of the lighter moments of the flight. After circling over Berlin for an hour or so, the Hindenburg flew over Tempelhof airfield to drop off some sacks of mail, much sought-after by stamp collectors for the special onboard Olympic flight cancellation. The sacks were attached to parachutes and dropped from one of the hatches that lined the airship’s belly.

In the course of this, there occurred a mishap in which one of the parachutes failed to open. The mail sack slammed into the ground and burst open. The wind then blew the letters and cards across the entire airport. There was a great deal of laughter as we saw how the airfield workers chased down the individual letters.

On one of the season’s final flights back from South America, Balla would recall another yet momentous event:

On the evening of the second day, we were told that on our homeward flight we would meet up with the Graf Zeppelin over the ocean. Everyone now waited eagerly for this encounter. Suddenly we saw a tiny light appear off the port bow, which grew bigger and bigger. From the ship, we saw nothing yet because of the darkness. Soon, however, there were more and more lights, and now we flew past each other about 300 meters apart. I leapt for the light switches and turned them on and off several times to convey our greetings. Immediately, the people on the Graf Zeppelin went with the same tactic and blinked across at us. We flew a few circles around our sister ship, and they did likewise. This unique meeting so far from home lasted maybe 10 minutes, and then each ship resumed its original course, one toward Brazil, and the other toward Frankfurt.

As he recorded his experiences in his journal, Balla would also make note of many of the various celebrity passengers who flew with them, particularly along the North Atlantic route to and from the United States. Former world heavyweight boxing champion Max Schmeling flew twice with them. Schmeling first traveled aboard the Hindenburg on his way back to Germany following his June, 1936 victory over Joe Louis as both boxers vied for a shot at the reigning world champion, James Braddock. Balla would later recall Schmeling as being very gracious, signing autographs for his fellow passengers and spending a lot of time enjoying the view from the observation windows.

of the USS Los Angeles following their arrival at Lakehurst in August of 1936.

Schmeling returned to the States aboard the Hindenburg in August of that year, on the same flight as another celebrity – silent film legend, Douglas Fairbanks and his new wife, Lady Sylvia Ashley. Balla would remember the couple not so much for Fairbanks’ fame as a former Hollywood swashbuckler, but because of their six-month old Scottish terrier, Bobby. Bobby, rather than being kept in the ship’s kennel area, was allowed free run of the passenger area, much to the dismay of the stewards. Balla would later describe him, quite bluntly, as ”…a naughty little puppy who left his calling cards for us all over the ship.”

Balla would also remember the special VIP flights that the Hindenburg would occasionally make. In June of 1936 Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, who ran the German industrial giant, Friedrich Krupp, AG, chartered the Hindenburg to carry himself and 50 others, including family members and Krupp AG officials on a sightseeing flight over Switzerland. At the end of the flight, which afforded an unparalleled aerial view of the Alps and the Swiss countryside, Herr Krupp presented each member of the Hindenburg’s crew with a pair of cufflinks made of genuine Krupp steel, which Balla later described as being “more valuable to me than if they had been made of gold.”

During the Hindenburg’s last visit to the United States in October of 1936, a VIP flight was arranged as a way of courting financiers and influential business and political leaders for a planned German/American international airship service. The day cruise over the colorful autumn New England countryside came to be known as the “Millionaires’ Flight”, and it was later said that the combined worth of the passengers exceeded a billion dollars. Balla served such luminaries as Nelson Rockefeller and Eddie Rickenbacker a sumptuous lunch that featured swallow’s nest soup, Rhein salmon, tenderloin steak in goose liver sauce and fine wines and champagne. Over the course of the flight, Balla added quite a few new signatures to his autograph book – which ended up being lost with the rest of his personal effects in the disaster at Lakehurst the following spring.

As the flight season drew to a close, Wilhelm Balla’s love of airship travel had grown to the point where he began to think about the future and consider whether there might be roles for him beyond that of a steward.

On one of the last flights of 1936, I asked Captain Lehmann if I might eventually have the possibility of becoming an airship helmsman. He conceded me an opportunity if I were to undertake the necessary studies to gain requisite skills, which would include attending the navigation school in Hamburg. I was overjoyed by this proposition.

Wilhelm Balla was, of course, aboard the Hindenburg’s first North American flight of 1937 when it left Frankfurt on the evening of May 3rd. It was a fairly unremarkable flight, except for the head winds and cloudy skies that persisted throughout the voyage. Three days later, on the evening of May 6th, the Hindenburg arrived over the airfield at Lakehurst, NJ, approximately 12 hours behind schedule.

Balla was downstairs on B-deck, and made his way up to the dining room to watch the landing maneuver. He stopped by the bar and asked bar steward Max Schulze if he wanted to come along. Schulze, however, was busy cleaning the bar and opted to stay behind. As he began climbing the stairs to A-deck, Balla encountered the ship’s new stewardess, Emilie Imhof, who had just been hired the previous November. He asked if she wanted to come on up to the dining room with him, since it was her first flight to North America. She also opted to stay downstairs, as she had to get the linens changed in the new bank of passenger cabins that had been installed on B-deck the previous fall. Balla continued on up to the dining room, not realizing that he would see neither of them alive again.

He made his way to the observation windows that ran alongside the dining room, and found a spot near the forward-most window, through which he watched the airship’s landing ropes drop and the ground crew pick them up. As he politely stood aside to allow some of the passengers to get a better look, he suddenly heard a muffled explosion and felt the ship give a sharp jerk.

The floor tilted as the stern of the ship dropped to the ground, and Balla fell to the floor, pulled by two nearby passengers who had also lost their footing. He heard another explosion closer to the passenger compartment, and thought to himself that he'd rather break his neck jumping out a window than to burn alive. He stopped his slide aft by grabbing hold of the handrail, pulled himself toward a nearby window, and noticed passengers beginning to jump out of the windows as the ship grounded itself. He looked aft and saw one of the passengers, Mrs. Matilde Doehner, toss her two young sons out of the ship. Balla himself leaped out a window from a height of about 20 feet, landed in the sand and got up to try and help the passengers still trapped in the ship. When he went to get up, however, he realized that he'd twisted his right ankle and was having trouble standing up on it.

Balla saw 14 year-old Irene Doehner leap from one of the other windows and limped over to help fellow steward Eugen Nunnemacher put out the fire on her clothes and in her hair. The two young Doehner boys, Walter and Werner, were standing nearby crying, and Balla accompanied them to a nearby ambulance. Rescuers tried to get Balla to get into the ambulance with them, but he refused to go, believing that he should instead stay and try to help. But by then, anyone who could be pulled alive from the wreckage was already being taken to the infirmary. Other than his sore ankle, Balla was virtually unharmed. He was eventually taken to the air station’s infirmary where his foot was examined and taped up, and then he went over to the airship hangar where he sent a telegram home to his wife: “Bin gesund” – “I’m well.”

Wilhelm Balla stayed in the United States for nine days following the disaster. The day after the crash, he returned with other crew survivors to the Lakehurst air base in order to help identify the bodies of the fire victims. He testified before the Board of Inquiry on May 14th, and the following day he returned to Germany with a group of fellow crew survivors (mostly stewards and kitchen staff) aboard the steamship Europa. Throughout the rest of his life, Wilhelm Balla was convinced that an airship filled with helium rather than inflammable hydrogen would prove to be the safest, most comfortable mode of transportation in the world.

Following his return to Germany, Balla and his wife moved from their home in Walldorf and returned to Munich, where Wilhelm continued to work in restaurants until Europe once more descended into war. He was drafted into the Wermacht (regular army) in 1940 and, possibly due to his service aboard the Hindenburg, was assigned to a Luftwaffe unit and stationed in Norway for most of the war.

In 1941, while Balla was home in Munich on leave, he invited his youngest brother, Helmut, for a visit. Since Helmut was 15 years old and almost finished with school, Wilhelm asked him what he intended to do after graduation. Helmut replied that he’d probably look for an apprenticeship as a metal worker, so that if nothing else he could find work at the coal mines where their father worked. Wilhelm suggested that he might be able to use his connections in the restaurant business to help Helmut to get a waiter’s apprenticeship in one of Munich’s finer hotels. Helmut gladly accepted, and once he had graduated school the following year he found an apprenticeship at the Regina Palast Hotel. During this time, he lived with Wilhelm and his wife, Tina – though Wilhelm was only home from the war occasionally when he could get a furlough.

Helmut and Willy Balla in Odeonsplatz in Munich in 1941

Meanwhile, the war took its toll on the Balla family. Wilhelm’s brother, Heinz, was drafted into military service in December of 1940. The following summer, following Russia’s declaration of war on Germany, Heinz Balla was sent to the Eastern Front. Here, he was badly wounded in combat and died in a field hospital on August 10, 1941, at the age of 21.

In late 1942, Wilhelm’s 19 year-old brother Alfred was also drafted into service, and was immediately sent to the Eastern Front, without being given even a short leave to visit his family before his transfer. Two weeks later, Alfred Balla, like his older brother Heinz before him, met his “Heldentod für Führer, Volk und Vaterland” (a phrase that all too many Germans were becoming familiar with, an impressive-sounding yet rather hollow official government condolence on the loss of their sons and brothers) when he, too, was killed in battle.

Heinz Balla Alfred Balla

1920-1941 1923-1942

Meanwhile, the Balla family could take some genuine consolation in the fact that Wilhelm was still stationed up north in Norway, far from the worst of the fighting and unlikely to meet his “heroic death for Führer, countrymen and Fatherland.” And yet, the war was not yet done with their family. Castrop-Rauxel was in the heart of the Ruhr Valley, a key industrial area with numerous coke plants, steelworks and oil refineries, as well as the coal mines in which Wilhelm’s father, Gottlieb Balla, had spent his life working. This made the Ruhr a prime target for strategic bombing by the Allies throughout the war. On the night of August 6-7, 1944, as sirens announced the approach of yet another formation of Allied bombers, Gottlieb’s wife, Wilhelmine, had taken their three daughters to the local air raid shelter, while Gottlieb and his youngest son, 15 year-old Günter, hid in the basement of the family home.

On this particular night, although the Balla family did not know this at the time, the bombers were targeting the Krupp Oilworks and the rail yards in Wanne-Eickel, about five miles away. When the drone of the bombers had faded away into the distance and the sound of flak had subsided, Gottlieb decided to take a look upstairs to make sure that nothing was on fire, since the Allies were known to drop incendiaries along with their regular explosive bombs. Just as Gottlieb emerged from the basement, a single stray bomb – apparently the only bomb to fall on Castrop-Rauxel that night – exploded directly in front of the Balla home, destroying most of the house and killing Gottlieb Balla instantly.

From left: Günter, Wilhelm, Hermann, Helmut and Fritz.

Fortunately, Wilhelm Balla’s Luftwaffe unit saw no combat during his time in Norway, and it was during this time that he began to write down his memoirs of his year and a half as a Zeppelin steward. However, fate seemed determined to take just one more shot at the Balla family. Just before the end of the war, with Vienna besieged by Russian troops, Balla was transferred to Austria where he ended up being captured by the Russians. With the end of the war virtually days away, instead of preparing to return home to Tina and the rest of his family, Balla was instead sent to a labor camp in Siberia, where he would spend the next five years.

Wilhelm Balla (indicated by X) and his comrades on the day they were

released from their captivity in a Siberian labor camp, November 17, 1946.

Wilhelm Balla was finally released from Russian captivity and returned to Germany in November of 1947, where he spent some time at a rest home for returning POWs in Abtsee bei Laufen, in southeastern Bavaria. Once he had taken some time to recuperate from his long and grueling imprisonment, Balla returned to the restaurant business as a sales representative. He continued to make a good living for himself and his wife, and eventually retired in 1977 at the age of 65.

Wilhelm Balla, circa 1950s Willy and Tina Balla, 1961

On May 7th, 1988, 51 years almost to the day following his narrow escape from the Hindenburg disaster, Wilhelm Balla passed away in Munich from a liver ailment at the age of 76. He and Tina had been together for more than half a century.

My deepest thanks to Helmut Balla, Wilhelm Balla’s youngest brother, for providing me with a wealth of information and photos that allowed me to greatly expand upon what had been a comparatively brief article. Helmut was kind enough to send me copies of family photos and a recent Zeppelin Museum publication (available HERE) that included an edited version of Wilhelm Balla’s journal, translated excerpts of which I’ve included here. Helmut also sent me a copy of his own autobiography, “Biografie eines 84-Jährigen” (available HERE), a fascinating look at his own life and a source of valuable information about Wilhelm and the rest of the family. In addition to the photos and books, Helmut has also been very generous in corresponding with me via email to clear up various questions that have come up as I’ve assembled the information presented here. Ein herzliches Dankeschön, Helmut!

8 comments:

I have a signed autographed photo from him on a photo of the Hindenberg. It was good to read about his history

Herr Balla does seem to have been a really interesting fellow. I would have loved to have had the opportunity to sit down and chat with him.

De superbes données peuvent être trouvées sur votre blog Web. Continuez votre bon travail.

Thank you so much for caring about this content and to your reader. Good job man.

The text was neat and readable. Great blog you written here. Thanks for blogging.

I read articles online very often, but I’m glad I did today. This is good! Excellent

I will ensure that I bookmark this blog and may come back from now on. Thanks..

Very value able post, I read the whole story when I start reading it.

Post a Comment