Crew Member

Age: 27

Hometown: Sylt, Germany

Occupation: Navigator

Location at time of fire: Control car - navigation room

Survived

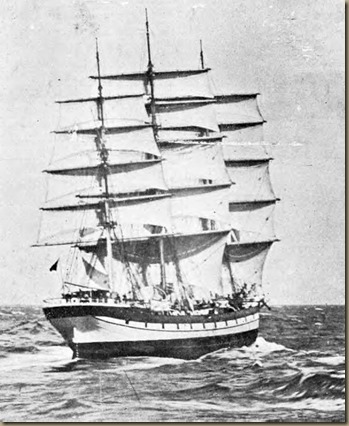

Christian Nielsen was a navigator who normally flew on the LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin. He was born on April 28, 1910 on the North Frisian island of Sylt. When he was 16 years old, he spent two years apprenticing as a seaman, and then beginning in April of 1928 he sailed the world as a merchant marine. Nielsen signed on with the F. Laeisz shipping company, and served as an able-bodied seaman aboard the Pinnas, a three-masted, full-rigged ship. The Pinnas had been purchased by F. Laeisz in 1911 as the Fitzjames from the W. Montgomery company of London.

In April of 1929, the Pinnas, under the command of Captain L. Lehmann and with a crew of 25, Christian Nielsen among them, rounded Cape Horn, bound for the west coast of South America with a load of cement, coal, and general cargo. The Pinnas had been fighting hurricane-force winds for two weeks and making very little headway. Suddenly, the wind dropped, leaving heavy swells that caused the ship to roll up to 50 degrees in either direction. After having weathered 14 days worth of extremely high winds, the heavy rolling proved too much for the Pinnas. Her foremast and mainmast both gave way, breaking a few feet above the deck. The mizzenmast also cracked just above the top, and the mizzen topsail and yards dropped to starboard. The Pinnas was now almost completely at the mercy of the sea.

The crew set to work cutting down the remains of the steel mizzen topmast, which had not completely parted, and which now hung against the side of the ship and threatened to damage the hull plating. Once the topmast had been cut away, the crew rigged an emergency aerial to the remains of the mizzenmast so that the radio officer could send an SOS.

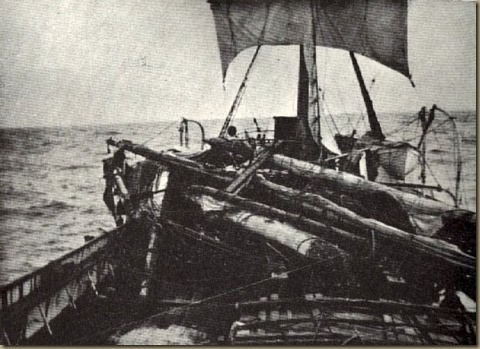

This remarkable photograph shows the extent of the damage suffered by the Pinnas. View is looking aft, across piles of wrecked masts, sails, and rigging, with the remains of the mizzenmast still rigged in the background near the ship's stern.

This remarkable photograph shows the extent of the damage suffered by the Pinnas. View is looking aft, across piles of wrecked masts, sails, and rigging, with the remains of the mizzenmast still rigged in the background near the ship's stern. The Pinnas' distress signal was picked up on the evening of April 22nd by the Chilean steamer Alfonso, which was bound for Punta Arenas. The captain of the Alfonso, Jorge E. Jensen Hansen, made haste for port, and informed the local authorities in Punta Arenas of the situation. The Alfonso received orders to load up with fuel and provisions and to set sail immediately to aid the Pinnas.

At dusk on April 24th, the Alfonso reached the Pinnas' location, about 200 miles west-southwest of Cape Horn. They found the German ship with her masts, sails, and rigging on her deck, with the crew trying to use the remaining mizzen sail to hold the ship into the wind, so that it wouldn't continue to roll on the rough seas. Captain Jensen hoped to be able to approach the Pinnas so as to lend assistance, but the weather had worsened again, with high winds and hail making a close approach too dangerous. The Alfonso, therefore, remained nearby for almost three days, waiting for weather conditions to improve.

Finally, on the morning of April 27th, the weather eased up somewhat and Captain Lehmann of the Pinnas radioed the Alfonso with an urgent request for assistance. The Pinnas was rapidly taking on water, and the decision had been made to abandon ship before the hull began to break up. Captain Jensen tried to bring the Alfonso alongside the Pinnas to rescue the crew, but the Pinnas was still rolling too badly.

Instead, Jensen ordered second mate Enrique Imhoff to take five men and one of the Alfonso's boats and row across to the Pinnas to effect a rescue. Since the rolling of the dying ship made an approach from either side impossible, Imhoff decided instead to row around to the Pinnas' bow. A pilot ladder was lowered from the Pinnas' bowsprit, and Imhoff and his men safely transferred the Pinnas' crew to the Alfonso in two trips, with Captain Lehmann being the last to leave his ship. Once the Pinnas' crew were all safely aboard, the Alfonso returned to Punta Arenas. The Pinnas herself was left adrift, and presumably sank somewhere off the southwestern coast of Chile.

Along with the rest of his crewmates, able-bodied seaman Christian Nielsen survived the wrecking of the Pinnas. He had suffered a broken jaw during the shipwreck, but one of his fellow sailors, F. Steffans, managed to set Nielsen's jaw using a piece of wood. Many years later, Nielsen's son Rink served as second officer on a Laeisz ship on which Steffans was also serving as a boatswain.

Nielsen and his crewmates spent the next two weeks recovering in Puntas Arenas, then boarded a steamer back to Germany.

(An excellent, detailed account of the wreck of the Pinnas and the rescue of her crew by the Alfonso, written by Chilean Contralmirante Roberto Benavente, can be found HERE.)

Later that year, in July of 1929, Nielsen signed on with the crew of the luxury yacht Orion. Commissioned by wealthy American textile magnate Julius Forstmann and built at the Krupp shipyards in Kiel, the 333-foot Orion spent seven months, from November 1929 until early June of 1930, cruising Forstmann's family around the world. Christian Nielsen was part of the Orion's crew of about 55 (depending upon the leg of the voyage in question.) The Orion was later sold to the US Navy in 1940, refitted as a gunship, and renamed the USS Vixen. It served as the flagship for the Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet throughout World War II.

In 1931, Nielsen received his officer's patent papers, and in 1932 he was similarly certified as a ship's radio operator. That same year, he received training in aerial navigation, and then in 1933 he trained as a pilot. In October of 1933, Nielsen enlisted in the German Navy, becoming an officer by 1935. He then transferred to the Luftwaffe in October of 1935 where he received further aviation training.

Just after the New Year, in January of 1936, Christian Nielsen retired from active military duty and was hired by the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei. He and his wife Maria, pregnant with their first child, moved from Sylt down to Friedrichshafen. There, Nielsen joined the crew of the Graf Zeppelin, which was making regular passenger flights to South America. By early 1937, Nielsen was serving as one of the airship's navigators.

On the Hindenburg's first North Atlantic flight of 1937, Nielsen was flying on the Hindenburg to observe the navigational techniques that had been developed on the newer ship. He augmented a navigation crew consisting of Franz Herzog, Max Zabel, and Eduard Boetius - who was, coincidentally, from the North Frisian island of Föhr, right next to Nielsen's home island of Sylt.

As the Hindenburg approached the mooring circle at Lakehurst at the end of the flight on May 6th, Nielsen was at his landing station in the navigation room at the center of the control car. Shortly after 7:00 PM, Eduard Boetius sounded the ship's signal for landing stations. Captain Albert Sammt, the watch officer on duty, then called Boetius to take over on the elevator wheel, and Nielsen sounded the second landing stations signal a couple minutes later. Nielsen was standing on the port side of the navigation room along with Max Zabel, and they watched the ground crew take up the yaw lines after the lines were dropped from the ship's bow. As a gust struck the port beam of the ship and the portside yaw line tightened, Nielsen saw the landing crew giving ground as the ship drifted to starboard.

Suddenly, the ship gave a violent jolt which threw Nielsen against the aft wall of the navigation room. Initially, he had no idea what the jolt was. His first thought was that the tightening portside yaw line had snapped, but then realized that the jolt had been too heavy for that. It was not until he pulled himself to his feet, with the ship dropping down by the stern, that he was able to get to one of the starboard windows and look aft, where he saw "a gigantic ocean of fire". The increasing inclination of the ship made it impossible for Nielsen to keep his footing, and he saw the drawers of the chart cabinet sliding open and spilling their contents across the floor. He slowly worked himself over towards the window on the port side of the navigation room as the ship neared the ground, looking for his chance to jump, but he held back for a moment when he noticed that they were still too high. He then looked forward and saw Eduard Boetius at the portside window next to the elevator wheel, also ready to jump. As the ship descended to within 10 to 15 feet of the ground, both men jumped, almost simultaneously.

Christian Nielsen (arrow) drops to the ground after jumping from the control car. Eduard Boetius is crouched on the ground just in front of him, having jumped from the window beside the elevator wheel a split second before Nielsen.

Christian Nielsen (arrow) drops to the ground after jumping from the control car. Eduard Boetius is crouched on the ground just in front of him, having jumped from the window beside the elevator wheel a split second before Nielsen. Nielsen landed safely and ran clear of the ship, just before it collapsed to the ground behind him. He looked back over his shoulder and saw that the entire ship was on the ground burning, then continued on until he was about 60 or 70 feet further away from the wreckage before turning around and running back to the passenger decks to assist in rescuing survivors. As he approached the wreck and prepared to climb up into the dining salon, Nielsen saw 16 year-old passenger Irene Doehner standing up on one of the portside observation windows, her hair and clothes afire. She jumped through a broken window, and when she landed Nielsen and two other rescuers quickly put out the fire on her clothes and hauled her to safety. Then, together with Boetius, Captain Walter Ziegler and steward Fritz Deeg, Nielsen climbed up into what was left of the portside dining salon. They located several passengers who had not yet made their way out of the ship, and led them to safety. Nielsen noticed that the passenger cabins in the center of A-deck were completely destroyed by fire, and left the wreckage soon afterward.

Christian Nielsen was virtually unhurt in the crash, and stayed in the States for slightly more than two weeks after the disaster. On May 19th, he testified before the US Commerce Department's Board of Inquiry into the Hindenburg fire, and within the next couple of days he sailed back to Germany with a group of his fellow surviving crew members aboard the steamship Bremen.

In September of 1939, with Germany officially at war, Nielsen volunteered for service with the Luftwaffe. He was assigned to a coastal patrol squadron in November of 1940 and stationed in France. On January 25th, 1941, Christian Nielsen was killed in action over the Bay of Biscay.

(Many thanks to Maiken Nielsen, Christian Nielsen's granddaughter, and her father, Rink Nielsen, for providing me with details about Christian's life. as well as Christian in his Luftwaffe trainer and the portrait photo that opens this article.)

1 comment:

Grateful ffor sharing this

Post a Comment