Crew Member

Age: 14

Hometown: Frankfurt, Germany

Occupation: Cabin boy

Location at time of fire: B-deck, Officers' mess

Survived

Werner Franz, born on May 22nd, 1922 in Frankfurt-Bonames, Germany, was a 14 year-old cabin boy on the Hindenburg's final voyage. His father was a switchboard operator in a Frankfurt hotel for many years, but he became ill in early 1936 and could no longer work. Werner's mother therefore had to take care of the household and also hold down a job. His 16-year-old brother, Günter, had been an apprentice waiter at the Frankfurter Hof since 1934, having gotten the job through his trade school. However, he didn't make nearly enough to support the family. Werner had left elementary school around Easter of 1936 to find work to help the family make ends meet.

Werner Franz spent months after leaving school looking for an apprenticeship. He was good with his hands, and eventually hoped to become an electrician or an engineer. Twice a week for three hours he'd go to trade school, but he was anxious to find work. He asked his brother to see if he could get him a position at the Frankfurter Hof, but Herr Wangemann, the hotel's director, though he thought very highly of the Franz boys, was unable to find him a position, as all apprenticeships were currently filled. The best he could do was to let them know if any apprenticeships opened up.

By autumn of that year, Werner was very discouraged. He wanted nothing more than to find a way to make some money to help his family. But there just wasn't any work for him. At 14 years old, he already knew what it was to be unemployed. Then, one day in mid-October, Werner's brother came bursting into the house, and excitedly told his parents that he'd spoken with Herr Wangemann and that the hotel director had recommended Werner for a job. Werner, sitting in his room dejected and brooding, had only to hear the word "job" before his ears pricked up and he heard his brother continue " as cabin boy on the Hindenburg."

His brother went on to say that Werner was to meet the next day with the Hindenburg's Chief Steward, Heinrich Kubis, at his apartment in Frankfurt. Werner was thrilled. Not only would he now finally be able to help his mother out by earning money, but he'd get to fly on one of the big Zeppelins that he and his friends had watched so many times flying out of the nearby Rhein-Main Airport. He'd be making a monthly salary of 60 marks (about $150, which was a considerable sum for a 14 year-old German to bring home in the late 1930s.)

Werner Franz and his father met with Heinrich Kubis the next day, and with the Hindenburg's commander, Captain Max Pruss, the day after that. He got the cabin boy job, and would serve on a probationary basis through the end of the 1936 flight season. His first flight was to have been a short test flight over Germany on October 18th, 1936, which was only a few days after his interviews. The flight was cancelled, however, and Werner Franz's first Hindenburg flight therefore ended up being a twelve-day round-trip voyage to South America beginning on October 21st.

As cabin boy, Franz served the ship's officers and crew. His duties would begin at 6:00 in the morning, when he would go to the kitchen to wash and put away any dishes that had been used by the night watch. Then he would set the table in the mess room for the first watch's breakfast, which began at 6:30. Since the mess areas were not large enough to accommodate the entire crew, meals were served in two sittings, and Franz had to clear and reset the mess tables in the very short time between each sitting. Lunch was served at 11:30and 12:30, there were half-hour afternoon coffee breaks at 3:30 and 4:00, and then dinner was served at 6:30 and 8:00. In between meals, Franz would make the beds in the officers' cabins, and then return to the mess area. At about 2:30 in the afternoon, he would have a short break, during which he would usually go to his bunk and rest for half an hour before returning to the mess area to prepare it for afternoon coffee. After dinner, Franz would telephone the control car to see if the evening watch needed coffee, and if so he would bring it to them in a coffee pot on a tray. His day's duties would be over by about 9:30 at night.

Franz spent his first flight to South America learning his duties and familiarizing himself with his new crewmates. During the Hindenburg's three-day stay in Rio de Janeiro, Franz met and befriended two nine year-old German children named Emilio and Gisela, whose parents ran an inn near the airfield. On Franz's second day in Rio, they all went horseback riding together. The day after that, the children and several of the Hindenburg's crew members spent the day at the seaside swimming and hunting for mussels.

On the return flight from Rio, Franz was already becoming used to his new duties, and had begun to get to know his crewmates. This time, as the ship neared the equator, Franz was working in the kitchen when one of the cooks sent him to the control car with a bucket and mop to "wash off the equator line." When he got there, the watch officer on duty told him with mock seriousness, "We're not quite there yet. Go on back and I'll let you know when you need to come back down here."

As Franz later wrote in his journal:

"Unsuspecting, I walked back along the gangway. Just before I got to the kitchen, I suddenly got a cold shower of water over my head. Suppressing a smile, I looked up and saw a cook with a large can in his hand standing on a girder above me. Other crew members appeared and stood there laughing until tears came to their eyes, because I looked so drenched. I then hurried aft to my bunk so that I could change my clothes."

Thus did Werner Franz receive the airshipman's version of the traditional sailor's equatorial baptism, as well as the acceptance of his crewmates. He was later given a special certificate in honor of his having "crossed the line."

Franz made two more South America flights in 1936 (November 5th through the 16th, and November 25th through December 7th) before the Hindenburg was laid up for its winter overhaul. On his second flight, Franz learned that the Hindenburg would be on its way to South America while her sister ship, the Graf Zeppelin, would be flying along the same route on its return flight. It had been estimated that the two ships would approach one another at around midnight on the third night of the trip.

Franz's bunkmate, steward Wilhelm Balla, woke him shortly before midnight, and Franz hurried aft to the emergency control stand in the Hindenburg's lower fin, where there were three round portholes on each side of the fin through which he could watch for the Graf Zeppelin.

"At first, you could see a couple of lights in the distance that you might mistake for stars. Then you saw the powerful beam from the directional searchlight on the bottom [of the Graf Zeppelin.] Now you could recognize individual parts of the ship: the control car, the engine gondolas, and the lower tail fin. Hundreds of tiny lights shone in the darkness as the giant ship passed us and the passengers waved to us."

In Rio, the Hindenburg had its usual three-day layover, and Franz once again spent time with his two young friends Emilio and Gisela. This time, they rescued a small dog who was being mistreated by one of the locals. Emilio and Gisela's family adopted the dog, and hereafter, when Franz would return to Rio on the Hindenburg, the dog would always remember him immediately and greet him like an old friend.

On his third flight to South America, and the last of the 1936 season, Franz was invited down to the control car to watch as the Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelin met in mid-ocean once again, this time during the day.

"As the Graf Zeppelin got fairly close to us, it made a slight turn and flew by us at a distance of about 300 meters with its motors at half throttle. Hereupon, the two airships flew a couple of circles around one another. After mutual wishes of "Have a good flight!" were exchanged, each ship continued along its course."

Franz knew that his two young friends Gisela and Emilio were on the Graf Zeppelin as it passed by, flying back to Germany for a visit. He therefore spent all of his free time in Rio this trip with his crew mates. One evening, Franz and several of his crewmates gathered outside of the window at Captain Pruss' quarters playing musical instruments (one of the stewards was using a saucepan as a drum, and Franz was wearing a sheet that one of the stewards had wrapped around him as a toga) as their way of inviting him out with them. Pruss joined them, and Franz would later recall it as having been a particularly fun evening.

At the end of this trip, back in Germany, Werner Franz was informed that he had passed his probationary period and was permanently hired by the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei as an official member of the Hindenburg's crew.

On its return to Germany after this flight, the Hindenburg was laid up in its hangar in Frankfurt for the winter, where it would receive a complete overhaul. The ship had logged over 3,000 flight hours in its first year of operation, and its designers wanted to see how it had held up, and to perform any repairs or improvements that were deemed necessary. Werner Franz, with his natural mechanical skills, was asked to take part in the overhaul. He performed minor assistant jobs as needed, and in the process he learned the layout of the Hindenburg in much greater detail than before.

In March of 1937, the Hindenburg made a couple of test flights, including one in which the famous German flying ace, General Ernst Udet, attempted to hook his airplane onto a special trapeze that had been installed on the lower hull of the Hindenburg. The US Navy had perfected this on their last two Zeppelins, with a special hook installed atop the airplane that the pilot would use to lock onto a trapeze extended below the airship, and the DZR planned to incorporate a similar hook-on airplane to their passenger airships to allow for in-flight pickup of mail and passengers. Udet's hook-on experiments would be the first step toward this.

Werner Franz was, of course, excited to see General Udet in person, and made note of the experience in his journal:

"All of the crew, those who weren't on watch at the time, watched through the lower windows as the airplane flew about half a meter below the ship's hull at the same airspeed as the airship, and with a very short distance between the hook and the trapeze. Then, Udet gradually increased his speed and approached the trapeze. This was the pivotal moment. We were all on edge: Would it work or not? There – a jolt, and the airplane hung there with its engine shut down, swinging to and fro, supported by its arrester hook. Everyone gave a sigh of relief, and Udet waved to us, laughing. Then he pulled a lever, and the airplane went into a glide. General Udet repeated this several times."

(In fact, General Udet had some difficulty in making his first hook-on attempt, bouncing the arrester hook off of the trapeze several times before successfully hooking onto it. This was most likely due to turbulence near the trapeze, and to the fact that the Focke-Wulfe Stieglitz that Udet was flying was simply too light an airplane for the job.)

On March 16th, 1937, the Hindenburg made its first round-trip South American flight of the year. The ship then spent several more weeks in its shed in Frankfurt, during which construction was completed on nine new passenger cabins that had been added to the ship. There followed a pair of test flights over the Rheinland on April 27th, and then preparations were made for the Hindenburg's first North American flight of the year.

It would be Werner Franz's first trip to the United States. Lakehurst, NJ, where the Hindenburg would land, was a short distance from New York City, and Franz was hoping for the chance to go into New York for the afternoon while the ship was being refueled for its return flight.

The Hindenburg left Frankfurt for Lakehurst on the evening of May 3rd, 1937. The flight to the United States was shorter than the flight to Rio de Janeiro by at least a day, and by the morning of May 6th the Hindenburg was flying down the northeastern coast of North America. Franz's shipboard duties had become routine by now, and he had settled comfortably into his new job. He had gotten to know his shipmates, who now considered him one of their own, and he had enjoyed finally meeting Captain Ernst Lehmann, the well-known airship captain who had worked with Count von Zeppelin in the early days before the war, and who had commanded both the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg before taking the post of Director of Flight Operations for the DZR and turning over command of the Hindenburg to Captain Pruss shortly before Franz was hired the previous year. Lehmann was aboard as an observer on this flight, and had given Werner Franz a friendly nod that morning as Franz served him his coffee.

The Hindenburg reached New York City in mid-afternoon, and it made a wide circle around the city so that its passengers could get a good look at the world's largest city from the air. Franz was in the officers' mess as the ship reached New York, and watched the city below through the mess room's windows:

"Since we had already passed over the steamship docks, we saw nothing but an ocean of buildings far and wide. Elevated trains, streetcars, and busses crisscrossed the wide streets, between which wound countless smaller automobiles. The sidewalks were swarming with people, like an anthill. Now and then you could see a subway train coming up from underground."

Delayed by headwinds over the North Atlantic, the Hindenburg was running half a day behind schedule. They had been scheduled to land at dawn on May 6th, but instead would be landing closer to sundown. The ship had already flown over the landing field at Lakehurst at about 4:00 in the afternoon, but with thunderstorms approaching the air station, Captain Pruss had decided to cruise along the New Jersey coast until the weather had cleared. Franz still hoped that he would have the chance to go into New York with some of his crewmates before the return trip, but it was looking less likely. Still, he did his dishwashing as quickly as he could so that perhaps there would be time. As he put the dishes away in their cabinet, he looked out of the officers' mess windows and saw on the ground below a pair of boys who were pedaling furiously, trying to keep up with the airship.

Then, at about ten minutes past 7:00, he heard the signal for landing stations as it sounded throughout the ship. About ten minutes later, he heard one of the crew members (radio operator Franz Eichelmann) relay an order from the control car via the telephone in the kitchen foyer that six men were to go forward to the ship's bow in order to help bring the ship into trim. Young Franz had been hoping to join them, because the windows in the Hindenburg's bow provided such an excellent view, but he still had dishes to put away. Disappointed, he stayed behind in the officers' mess.

Werner Franz had a coffee cup in his hand and was just reaching into the cupboard to put it away when he heard a dull thudding sound and felt the entire ship shake. He froze as the dishes he had put away were all jolted out of their cabinet and crashed to the floor. The ship began to tilt steeply aft, and Franz ran to the door to the keel walkway and looked out into the hallway. He glanced aft and saw, to his horror, a mammoth ball of flame rushing toward him. He instinctively began to back-pedal away from the fire and toward the bow. Franz looked around to see if any of his crewmates were there, but he could see no one. As the ship tilted even more steeply, he began to slide aft toward the flames, and grabbed at the ropes that lined both sides of the keel walkway. Dazed, he hung on as the fire roared through the hydrogen cells above him and the ship's hull jarred and shook as it slowly crashed to earth.

Suddenly, and with eerie similarity to his "crossing the line" initiation from his first flight to South America, Franz was doused with water pouring down on him along the inclined keel. A water ballast tank set alongside the walkway about 40 feet forward of Franz's position had slipped off its mountings and ruptured, sending its contents aft. The water soaked Franz's clothes, not only effectively shielding him from the heat, but also snapping the stunned boy back to his senses. He began to look for a way out of the ship.

As he held onto the ropes and felt the fire behind him growing hotter, Franz began looking for a way out of the burning Zeppelin. Just forward of him, on the starboard side of the keel walkway, there was a large hatch through which he and the kitchen crew provisioned the ship with food. He tried to make his way along the walkway toward the hatch, but the keel was still at too steep an angle, and he had to wait until the bow began to sink down so that he could climb those few last feet forward.

When the ship finally began to drop down in the front, Franz pulled himself forward and sat on the catwalk next to the hatch. In the red glow of the fire, Franz kicked at the hatch with both feet and knocked it open. Through the hatchway he saw the ground coming quickly toward him. When the ground was only a couple of meters away, Franz jumped. Suddenly, the ship began to rise up above him again as it rebounded off the landing wheel beneath the control car. Franz was therefore given a few seconds in which to run out from under the ship. His first instinct as he jumped had been to run with the wind, but as he landed he saw the flames being blown ahead of him, and immediately turned around and ran into the wind instead. As the Hindenburg's hull hung momentarily in the air above him, Franz ran as fast as he could toward the port side and just barely got out from underneath the wreck before it crashed to the ground behind him.

Amazingly, Werner Franz was almost completely uninjured – "Wet, but alive," as he would later say.

Diagram of Werner Franz's miraculous escape from the Hindenburg. 1.) Standing in the officers' mess on B-deck, Franz feels a sharp jolt run through the ship as the tail bursts into flame. 2.) Franz runs out into the hallway and, looking aft, sees the fire burning. 3.) Franz backpedals away from the fire and out into the open keel walkway. He holds on as the ship inclines sharply. Water from ballast storage tank (red star/f1) flows aft and soaks Franz. 4.) As the ship begins to level out, Franz moves forward to hatch and jumps.

Diagram of Werner Franz's miraculous escape from the Hindenburg. 1.) Standing in the officers' mess on B-deck, Franz feels a sharp jolt run through the ship as the tail bursts into flame. 2.) Franz runs out into the hallway and, looking aft, sees the fire burning. 3.) Franz backpedals away from the fire and out into the open keel walkway. He holds on as the ship inclines sharply. Water from ballast storage tank (red star/f1) flows aft and soaks Franz. 4.) As the ship begins to level out, Franz moves forward to hatch and jumps.  The provisioning hatch through which Werner Franz escaped, seen here serving its normal function. (photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

The provisioning hatch through which Werner Franz escaped, seen here serving its normal function. (photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)  Werner Franz (arrow) can just barely be seen dropping to the ground through the hatch. The ship's hull will rebound into the air momentarily, giving Franz just enough time to run to safety.

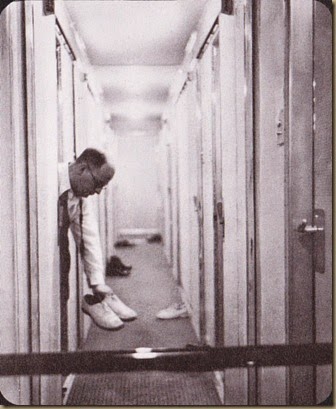

Werner Franz (arrow) can just barely be seen dropping to the ground through the hatch. The ship's hull will rebound into the air momentarily, giving Franz just enough time to run to safety. After he ran out from under the Hindenburg's hull, Franz kept running. Gradually, he slowed down and came to a stop when he was perhaps 40 meters from the wreck, and stood there in shock. Everything seemed unreal, and the men running toward the wreck to rescue survivors swam before Franz's eyes like ghosts. Chief Steward Kubis found him moments later. Kubis saw the confusion on the boy's face and said, "What are you standing here for? Go back to the ship and help!"

This snapped Franz out of his panic, and he turned around and returned to the wreck. As he got closer, he noticed the intense heat from the fire, and it finally occurred to him that he was soaking wet and freezing. But he continued on, looking for somebody to help. As he approached the wreckage, a sailor grabbed hold of him and tried to order him off the airfield. Franz could not immediately remember the correct words in English, so he pointed toward the burning airship and exclaimed, "Ich bin der cabin-boy vom Hindenburg! Ich bin doch der cabin-boy vom Hindenburg!"

Gradually the sailor realized what he was saying, clapped Franz on the shoulder and said to the other sailors nearby, "Hey, this is the airship's cabin boy!" The sailors crowded around him, amazed that the boy was not only alive, but barely scratched. Noticing that he was soaking wet, one of the men gave Franz his coat. But he was anxiously looking past the sailors toward the wreck to see if he could see any of his crewmates. Before long, two of the stewards came up and led him away by the arm. "Come on, son," they said, "There's nothing more we can do here."

Franz turned back and gave the sailor his coat back, and then followed the stewards to a waiting auto that took them toward the air station's hangars. Other survivors among the crew were beginning to gather there. An older gentleman who worked at the air base took Franz back to his quarters so that his wife could give the boy some dry clothes, and then Franz joined several of his surviving crewmates at the air station's infirmary to check in on the crew survivors who were among the more seriously injured. Eventually, he made his way over to the barracks, where uninjured crew survivors were being housed, and slept until late the next morning.

Initially, Werner Franz's name was mistakenly placed on the official list of those believed to be missing in the wreckage. Therefore many of the earliest newspaper reports had him listed as either missing or dead. He found out about this the next day when he saw the newspapers, and realized that once this news got back to Germany his parents would be devastated. He therefore had a telegram sent to them immediately, telling them that he was alive and uninjured.

The water ballast tank that soaked Werner Franz's clothes can be seen in this aerial photo of the wreckage. The tank's aft end has been knocked approximately 45 degrees in toward the keel walkway, where it dumped its load of water aft toward the spot where Werner Franz was located.

The water ballast tank that soaked Werner Franz's clothes can be seen in this aerial photo of the wreckage. The tank's aft end has been knocked approximately 45 degrees in toward the keel walkway, where it dumped its load of water aft toward the spot where Werner Franz was located. He was given permission by the commander of the Lakehurst base, Commander Charles Rosendahl, to go out to the Hindenburg's wreckage later that day in order to find a watch given to him by his grandfather that he'd had amongst his possessions aboard the ship. Accompanied by Lieutenant George F. Watson, the base public relations officer, Franz first looked for the officers' mess, thinking that he would perhaps find one of the dishes he had been putting away at the time of the fire. However, there was nothing left of the officers' mess – the crash and the fire had destroyed everything. He then went to the stern of the ship and picked through the rubble in roughly the area where his bunk had been (Lt. Watson later recalled that Franz walked almost directly to the correct spot the moment they entered the wreckage) and, amazingly, he found his watch. He took it, along with a scrap of the ship's framework as a souvenir.

That evening, and for the rest of his time in the United States, Franz stayed with Anton Heinen and his family. Heinen was a former Zeppelin commander who had emigrated to the United States and now worked for the US Navy, and he and his family lived in a house on the Lakehurst air base. They took Franz into New York to Wanamaker's department store to buy him new clothes, and did their best to make him feel at home.

Werner Franz and a number of his shipmates pose for news cameras in front of the Officers' Mess at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, on or about May 9th, 1937. 1.) Max Henneberg (steward); 2.) Fritz Deeg (steward); 3.) Jonny Dörflein (engine mechanic) 4.) Max Zabel (navigator); 5.) Severin Klein (steward); 6.) Eduard Boetius (navigator); 7.) Egon Schweikard (radio operator); 8.) Xaver Maier (head chef); 9.) Werner Franz (cabin boy); 10.) Rudolf Sauter (chief engineer); 11.) Wilhelm Balla (steward); 12.) Eugen Nunnenmacher (steward); 13.) Albert Stöffler (pastry chef); 14.) Wilhelm Steeb (engine mechanic trainee); 15.) Heinrich Kubis (chief steward); 16.) Captain Heinrich Bauer (watch officer); 17.) Kurt Bauer (elevatorman); 18.) Eugen Schäuble (flight engineer); 19.) Helmut Lau (helmsman); 20.) Alfred Grözinger (chef); 21.) German Zettel (chief mechanic).

Werner Franz and a number of his shipmates pose for news cameras in front of the Officers' Mess at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, on or about May 9th, 1937. 1.) Max Henneberg (steward); 2.) Fritz Deeg (steward); 3.) Jonny Dörflein (engine mechanic) 4.) Max Zabel (navigator); 5.) Severin Klein (steward); 6.) Eduard Boetius (navigator); 7.) Egon Schweikard (radio operator); 8.) Xaver Maier (head chef); 9.) Werner Franz (cabin boy); 10.) Rudolf Sauter (chief engineer); 11.) Wilhelm Balla (steward); 12.) Eugen Nunnenmacher (steward); 13.) Albert Stöffler (pastry chef); 14.) Wilhelm Steeb (engine mechanic trainee); 15.) Heinrich Kubis (chief steward); 16.) Captain Heinrich Bauer (watch officer); 17.) Kurt Bauer (elevatorman); 18.) Eugen Schäuble (flight engineer); 19.) Helmut Lau (helmsman); 20.) Alfred Grözinger (chef); 21.) German Zettel (chief mechanic). The following Tuesday, May 11th, Franz visited New York again, this time with a number of his shipmates. The coffins of the German passengers and crew killed in the disaster were being shipped home aboard the steamship Hamburg later in the week, and there was a dockside memorial service being held that evening.

Franz testified before the Commerce Department's Board of Inquiry on May 13th, 1937 – exactly a week after the disaster. When Lt. Col. Joachim Breithaupt, the German Air Ministry's representative on the German commission sent to the United States to take part in the investigation, was introduced to young Werner Franz, he would later recall that the young man's first question to him was, "Herr Oberstleutnant, when the next Zeppelin is ready, may I fly again with her?"

Werner Franz sits with Captain Walter Ziegler on the day of Franz's official testimony to the US Commerce Department's Board of Inquiry.

Werner Franz sits with Captain Walter Ziegler on the day of Franz's official testimony to the US Commerce Department's Board of Inquiry. (photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Franz returned to Germany two days later with other surviving members of the crew (mostly stewards and kitchen staff) aboard the steamship Europa. Before boarding the ocean liner at the docks in New York, Franz and several of his shipmates had time to see a movie at Radio City Music Hall. The Europa arrived in Bremerhaven on May 22nd, Franz's 15th birthday – which he had completely forgotten about until somebody at the dock reminded him of it.

Werner Franz (front and center) and his shipmates are met at the dock in Bermershaven by the Graf Zeppelin's commander, Captain Hans von Schiller (at right, in uniform). Albert Stöffler is at left, Heinrich Kubis (in hat and moustache) is just behind Franz, and Alfred Grözinger is just to the left of Kubis. (photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)

Werner Franz (front and center) and his shipmates are met at the dock in Bermershaven by the Graf Zeppelin's commander, Captain Hans von Schiller (at right, in uniform). Albert Stöffler is at left, Heinrich Kubis (in hat and moustache) is just behind Franz, and Alfred Grözinger is just to the left of Kubis. (photo courtesy of the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmBH Archive)Werner Franz survived WWII, which he spent as a Luftwaffe radio operator, and went on to have a long career repairing precision instruments for the German Federal Post Office. He also turned his lifetime love of competitive skating into a side career as a professional roller- and ice-skating coach. Franz trained many title-winning students throughout the years, including Olympic silver medalist Marika Kilius and her pair-skating partner Franz Ningel.

Werner Franz gave numerous interviews over the years to journalists and documentary crews about his experiences as the Hindenburg's cabin boy. He also made a few visits to the United States, the last of which was in 2004 when he was an honored guest at the opening of the new information center and museum at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station (by then renamed the Lakehurst Naval Engineering Station.)

Werner Franz (second from right) during his 2004 visit to Lakehurst, NJ, examining a copy of the May 9th, 1937 crew survivor group photo (shown above) with (from left) Siegfried Geist, Patrick Russell, and Andreas Franz.

Werner Franz (second from right) during his 2004 visit to Lakehurst, NJ, examining a copy of the May 9th, 1937 crew survivor group photo (shown above) with (from left) Siegfried Geist, Patrick Russell, and Andreas Franz.

Werner Franz passed away on August 13, 2014 at the age of 92. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving member of the Hindenburg’s crew.

Note: Much of the information about Werner Franz's life and his earlier flights (as well as many of the events of the night of the Hindenburg disaster itself) comes from the book "Kabinenjunge Werner Franz" by W.E. von Medem (Franz Schneider Verlag, Berlin, 1938.) Please be aware that, between possible errors in my own translation of portions of the book from the original German, coupled with the fact that I have not had available to me a second source from which to triangulate much of the information I gleaned from the book, there may be some inaccuracies in this article. Should any such inaccuracies come to light, of course, I will gladly correct them.

In addition, I was also very fortunate to have the opportunity to speak briefly with Herr Franz and his son Andreas during their 2004 visit to Lakehurst. I gave Herr Franz a copy of a group photo of him and other crew survivors (which I have also included in this article) and he was kind enough to share with me some memories of his old shipmates and of his experiences aboard the Hindenburg. It was a unique experience for me, and I will always be grateful to Herr Franz for his patience and generosity with a random fellow like myself who came up to him out of the blue holding a 67 year-old photograph. It's my hope that this article tells his story in as accurate and respectful a way as possible, and that it in some small way repays the kindness that he showed me.

![Willy-Balla---age-3-in-1915-lower-re[1] Willy-Balla---age-3-in-1915-lower-re[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhi56gpcHACETDAMsBMMOyvxHVztsy7Qz8pqdkK_9ALnK71sKpnYqDyLIs37uNh8FiGDDM7LSxFygDfkP5md-WKIItL_l900-FF4lhy5zuwmC9PkbKttV-84_rpKhOp1ix8npUsb79d4sE/?imgmax=800)

![Willy-Balla-feeding-the-pigeons---ci[2] Willy-Balla-feeding-the-pigeons---ci[2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiMU6AGnDqsAEWcO_eSC7h-jRqMwfpmlHTh0QLi8ZCf0AIW0q7IDsBnCg6YyeLKOF-472FzHd4nHP5kd6YmlJJjPkr5Nuuej4P4va0_FZP3AF05_DX7jszIA2WYzfBiNDHMKs1us5LCaJI/?imgmax=800)

![Wilhelm-Balla---equatorial-baptism-c[1] Wilhelm-Balla---equatorial-baptism-c[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKUUqBZPQOHsqSo9wXh3L6qQCglzUT9PYgkA6ghTOtNgZLajj_BiDROPcQOJ-5MB51mgNzA4s_oUNhaLeaknpkHonqUqaqKyp_Nc9a7HV6lPhCIUE1uSmH-0ZEX00bTifCWCJrCPYUrXY/?imgmax=800)

![Douglas-and-Sylvia-Fairbanks-with-Ma[1] Douglas-and-Sylvia-Fairbanks-with-Ma[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEikIGYGZcYM3gYrNQPF4mueVcvt6NApVGjj6A-TrScFa5qQBYOS69rmF3PrTH1RdQutcAVdUb6cz6InOOqeKCMseOxO19oyRoj2ziRLNEpb2XC3wUXXzprgjah-l-PVyFrsQE-zUMSWHKc/?imgmax=800)

![Wilhelm-Balla---1941-Deutsche-Wehrma[1] Wilhelm-Balla---1941-Deutsche-Wehrma[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjxUIQPd2gO0yIrCXMFZ9oZRc65rlKKW58l5P8k8dhQAcNRLu6EWZXM-dvfOmh7yeS6nABoCNK5C4mpPuyXlvrZ5gwKwNU8pKpvIosgs6siw-g55cEcgrVIhQl15BhUQHvNnLP_PDyy4J0/?imgmax=800)

![Balla-brothers-at-Fathers-funeral---[2] Balla-brothers-at-Fathers-funeral---[2]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjEOgrlQ0oqicJx-_XImQXkMbK3Qsvnauvel-HjNwSt0W_MfmHdVRgDRuPvnZuii5AQDzQUiV2GSw2O4zJFS3oJqlkN_yKYBA9S0AqAVTShw0R35lH7FqKYdSXPd6VJHabOV5TXEmxhiT0/?imgmax=800)

![November-17-1949---Return-after-5-ye[1] November-17-1949---Return-after-5-ye[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIYHFgKObNOpo9f8RfuWSK4HgOFrBSVt-PPoKF0WJyWGLUCRmU6v_5UU1OOsAwm7m4OISVo44uTdH3o1QpvI2UvNSLbREzvbZlUyOvKnx9-NNFPXwRkBVfd9aR_wZ496JeHdD1tUDcjiU/?imgmax=800)

![Wilhelm-Balla---circa-1950s-lower-re[1] Wilhelm-Balla---circa-1950s-lower-re[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiLqGclI3oSrlx0scORzooQ4WcAuojDflr5RrHYH-TqFskQOsQx3yMQyJIJ5fmrK1JJhBCBSBKAoZjiUB56NGO0chHcj6hRh6qXzK4G0Wjwk2Nt2mRAm6j44ps2sWU3g-8TC9zrRJWq_08/?imgmax=800)